In Conversation With is a new weekly series where we ask friends of the Museum to tell us about their favourite object – and what it means to them.

Michael Bywater is a broadcaster and writer of non-fiction. He is Cambridge-based and a favoured supervisor of the English Tripos’s Tragedy paper. Here he finds an ancient precedent for ‘One Man and His Dog’.

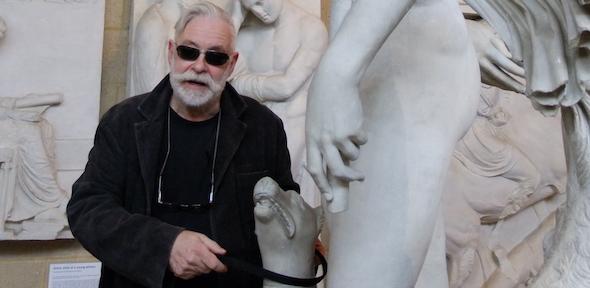

Michael Bywater with Meleager - and his dog.

'I hold no brief for the fellow in this tableau. I don’t really want to talk to him – it would just be the usual heroic nonsense – but I have been puzzled what it is about his statue so alive, and so absorbing?

'The fellow is a clearly dodgy swaggering sort of dude. You’d want to watch your step. The Fates put a curse on him, which should tell us something. They didn’t hand curses out like loukoumi. A curse meant something in the first millennium BCE.

'So, like most Greek heroes,1 he led an unfeasibly action-packed life, clanging and crunching with feud, slaughter, betrayal, sexual incontinence and cataracts of shed blood. And there he is: an affable-looking, athletic young man, captured for getting on for 2,500 years, in a warm breeze, with a hunting trophy – a peculiarly hellish-looking wild boar’s head, resting on what seems to be a stalk of giant broccoli – his spear, and his dog.

'Okay. The boar. Not just any boar. Meleager’s father was the noble vintner Oeneus, who learnt his trade from, of course, Dionysus.2 So. He moved in goddish circles. Unfortunately, Oeneus snubs Artemis, who sends a wild boar to terrorise the countryside and destroy the lives and livelihoods of the locals.3 This, the boar is good at.

'The boar having been killed,4 the general gore and horror resume. Sexism, computer-game warrior women (Artemis’s sidekick Atalanta, in this case), dog on the case, in goes the spear (the little stump in our copy here), plaudits for Meleager, various killings. Althaea, Meleager’s mother, triggers the Fates’ curse, thereby killing her son, selection of mourning women turned into guineafowl.

'Perhaps they got the better deal; presently Meleager dies and in Hades he meets Hercules and... complications ensue. Of course. So far, so good. But Meleager’s story gave birth to over 40 Roman copies or re-editions of the tableau here, even though none of the contemporary writers had anything to say about them.

'The attraction of the subject for Romans – the more or less naked Meleager, the boar’s severed head, the spear, the dog, the narrative of righteous cleansing of unclean savagery emanating from an angry god – is self-evident.

'But is it enough to explain either the profusion of statuary or the oddly compelling quality of all but the most gaudy or incompetent examples?5

'The very ordinariness of the piece may be the key to its immediate charm, and the deeper, longer-term effect it can have on the viewer. So... a fit young fellow with his dog and his trophy, who has done the community a service, stands there, neither triumphant nor exhausted, but... contained.

'He’s no superhero. Nor is he a fledgling demagogue. He’s looking away from us, neither boasting nor challenging.

'This is rare. Great men in marble are usually intent on their own business and/or the projection of their power. In the sculpture gallery, each of us, as we look, is reduced to an outsider. The sculptures are self-absorbed. Their accidentally-blank eyes can’t catch ours, nor would they want to.6

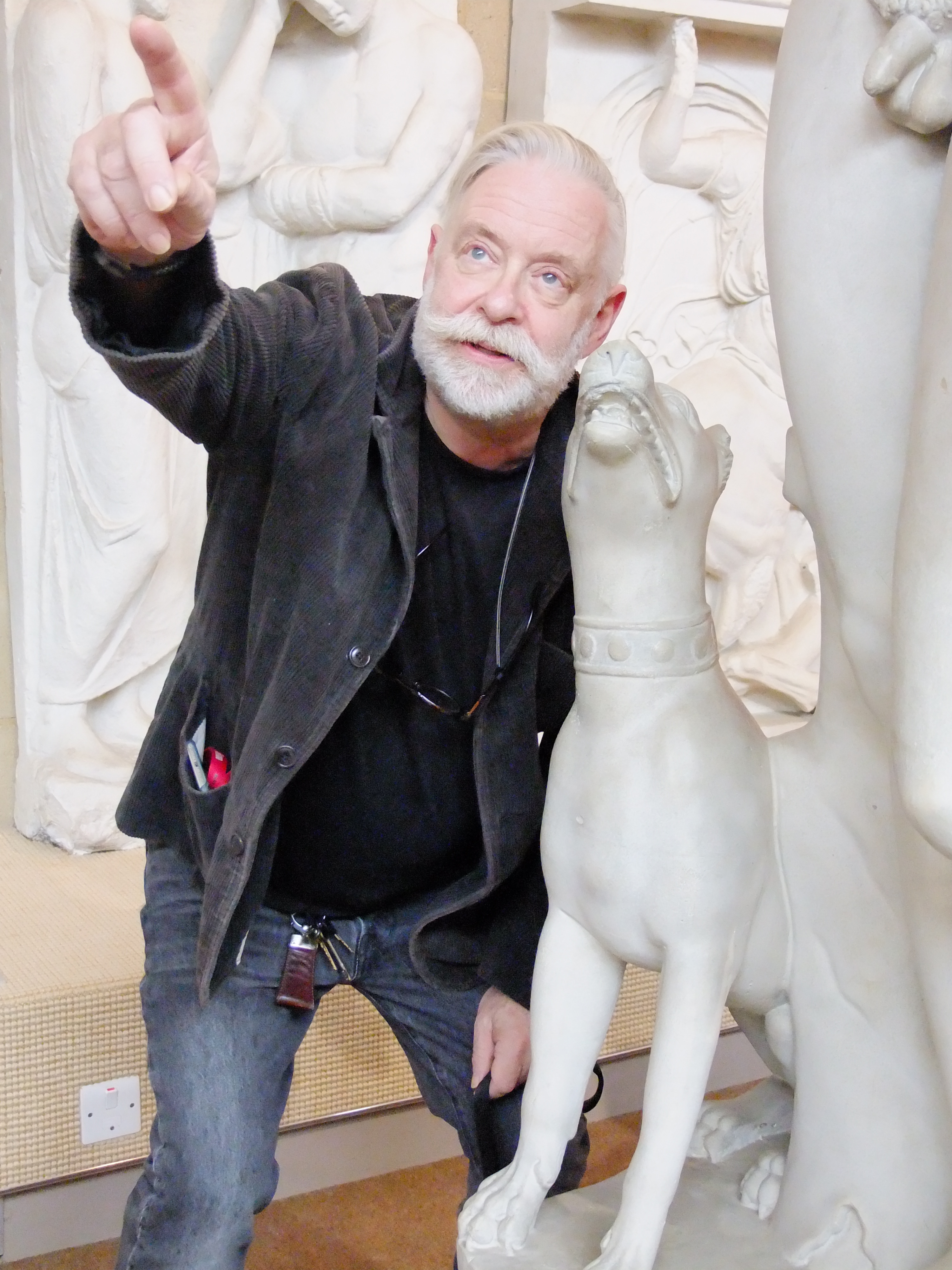

Michael Bywater and such a good doggy.

'But what happens in this portrayal is unexpected: we are given an ally, a co-conspirator: one who bridges the gap between statue and viewer. I mean, of course, the dog. He is bent on his master’s business; waiting happily for orders; whatever is next, this dog will enjoy it. He is like Kipling’s Four-Feet: “I am coming with you!”. Meleager is embracing his destiny; the dog, his sofos kunídion, his smart puppy, is simply exercising his profession: to watch his man and be ready. Now we can relax. We have distance and proximity at the same time. When we start to drift into... not “mindfulness”, which seems an unhelpful state to experiencing any art, but perhaps a kind of “absent-mindlessness”, then the work can speak to us, or, at least, catch our eye. Most of us go into galleries like teenagers going to a party: hoping hopelessly to find The One. If The One turns out to be a plaster dog - and a beautiful dog, too; look at his paw-bones, his poise, his deep chest, his taut proximity to his man – then so be it. Follow his eyes; see through them. Soon the stories will start to come down. The one that fascinates me is: What do Meleager and his dog make of each other?'

1 And an Argonaut, some say.

2 Though some suggest that Meleager’s real father was Ares, the brutal and unpopular god of War.

3 Not far-fetched; farmers protested in Rome very recently about a plague of boars who “destroy crops” and “will cause crashes”.

4 As Mr Mogg will excitedly observe, an example of the ablative absolute in English.

5 And there are plenty. There’s a nasty bronze and gold one in the Victoria and Albert Museum, an equally nasty one in the Louvre, a gold one in the Grand Cascade at the Peterhof in St Petersburg, not to mention a hideous zinc one at Osborne House, Isle of Wight, a present from Prince Albert to Victoria that makes one wonder whether he handed it over saying “If you don’t like it, they’ll change it; I kept the receipt”

6 The celebrated purity of white marble or patinated bronze which so seized aesthetes like Oscar Wilde, was the effect of time; they were, generally, gaudily painted and gilded.

Want to see Meleager (and his Dog) yourself? Michael's favourite cast can be found in Bay F.

Want to know more about Meleager (and his Dog) and our cast? Check out our research catalogue.

More In Conversation With

- Mary Beard and Aphrodite

- Oedipus (aka Rosy Sida) and the Nike of Samothrace

- Issam Kourbaj and the Children of Niobe

- Lyn Bailey and the Dying Gaul

- Sade Ojelade and Laocoon

- Classics Undergrads and Kouroi

- Katharine Russell and the Terme Boxer

- Emlyn and Farnese Hercules