Our plaster cast of the so-called Peplos Kore – painted in bright reds, greens and blues – is one of our best known and most loved exhibits.

But she was always intended to be a provocation.

Prof Robert M. Cook, the Curator of the Museum of Classical Archaeology who masterminded the purchase and painting of a restored cast of the Peplos Kore in 1975, wanted his brightly coloured innovation to make visitors think.

Was all ancient sculpture so brightly coloured? Would we look at the statues in the Cast Gallery differently if we saw them with their original paintwork? And why do we think of ancient sculpture as white?

What is a kore?

A kore (plural: korai) is a statue of a young woman used to mark graves or, more often, as a votive offering to the gods in the sixth and fifth centuries BCE. The word kore means 'young woman' or 'girl' in ancient Greek; it's a word classical archaeologists use to describe this type of Archaic sculpture.

Korai stand frontally, sometimes pulling at their skirts or offering out an object to their viewers with one outstretched hand. They are usually dressed in multiple layers, wrapped in fabric which may conceal or reveal the body underneath and which often falls in beautiful pleats creating a riot of different textures.

The original Peplos Kore

Athens, Akropolis Museum, no.679

Date: c.530 BCE

The statue now known as the Peplos Kore was found on the Athenian Akropolis in 1886, near a temple known as the Erechtheion. It was found in three parts over the course of several days which were not initially connected to each other: archaeologists assumed the head was too lively for the block-like body.

The Peplos Kore is 1.18 metres tall and is made of Parian marble, quarried not far from Athens. Traces of paint survived on the surfaces of the statue when she was found; they can still be seen, as dark areas of oxidisation, on the original in the Akropolis Museum. Like fourteen other korai discovered on the Akropolis, the Peplos Kore had been dumped in a pit as part of the renovations following the Persian destruction of the Akropolis between 480-479 BCE. By burying them on the Akropolis, the Athenians ensured these broken and damaged dedications remained sacred to Athena.

What is a peplos?

A peplos is a type of dress worn by women in Greece c.500 BCE. There was no tailoring in ancient Greece – so this particular type of dress was made of a big sheet of fabric, folded over at the top and wrapped around the body. It was pinned at the shoulders to keep it from falling down and often belted at the waist.

By the fifth century BCE, wearing a peplos had fallen out of fashion; it may even have looked slightly (and deliberately) out-of-date when the Peplos Kore donned it in the sixth century.

The Peplos Kore, as the name suggests, has traditionally been understood to wear a peplos. Indentations on the shoulders, just visible on our unrestored plaster cast (no.34), have been interpreted as an indication of addition of now-lost brooches.

The Painted Peplos Kore (plaster cast)

Cambridge, Museum of Classical Archaeology, no.34a

Date: 1975

The Museum of Classical Archaeology acquired a new cast of the Peplos Kore in 1975 from the plaster cast workshop in Dresden. Since the Museum already owned an unrestored cast of the sculpture, the Curator, Prof Robert M. Cook, made the decision to restore the new cast and to paint it as if its original colours were still preserved.

So little paint remains on the original that restoring her appearance was a tricky proposition which required some imagination. Cook based his interpretation on the surviving evidence of paint still visible on the original and on early watercolour drawings, published in 1887, by the Swiss painter Émile Gilliéron. But Gilliéron favoured washed-out and faded colours in his reconstructions – the bright (or, to some visitor's eyes, garish) colours of our Peplos Kore were a deliberate choice on Cook's part.

Cook reconstructed the Peplos Kore as wearing a red peplos, trimmed with a white and green pattern on its edges and with a vertical band of squares running down the front of the skirt. He interpreted the pleats at the bottom as a crinkly dress, called a chiton, worn underneath. The outstretched left arm, lost in the original, was reconstructed holding a spherical object, and a golden 'umbrella', called a meniskos, was added to her head – partly on the assumption that it would have originally protected the sculpture from birds, and inspired by the holes for a missing metal attachment.

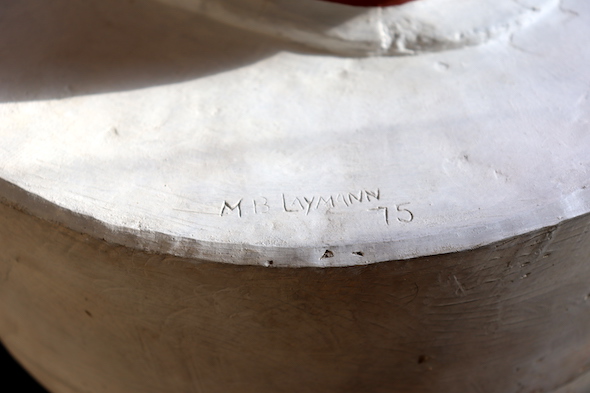

The painting itself was undertaken by a German gentleman, Herr M.B. Lehrman. It was the crowning glory of a long-standing collaboration with MOCA, during which Lehrmann added a surface coating to the casts to make them look less like plaster and more like stone. Herr Lehrmann (anglicised as Laymann) added his signature to the base of the painted Peplos Kore.

Where to find the Peplos Kore: Bay A

View the Peplos Kore on the online catalogue

Conservation

Repainted: 1996

Even a cast sometimes needs some tender loving care. In 1996, the painted cast of the Peplos Kore was repainted. The paints used to paint her in 1975 had faded and cracked.

Colour and Classical Sculpture

Today, we are accustomed to viewing Greek sculpture as bright white: clean and fresh marble is no doubt what we think of most when we imagine ancient Greek art. And yet, we have known since the end of the eighteenth century that the Greeks painted and adorned their sculptures.

The Roman author Pliny the Elder – famous for meeting his end during the eruption of Vesuvius which buried Pompeii and Herculaneum – wrote in the first century CE of how statues were coloured and polished to produce a full spectrum of effects upon their viewers.

In the later nineteenth century, excavations on the Akropolis in Athens began to produce statues on which traces of coloured paint could still be seen on the marble surface. The Peplos Kore was one of those statues.

Looking anew at colour

Did the original Peplos Kore really look like Cook's painted reconstruction? We don't know. Our painted version was an attempt to imagine what it might have looked like, based on the evidence available at the time.

But the real power of the bright paintwork of our version is to challenge our preconceptions of classical sculpture. Nineteenth century notions of the so-called 'Classical Ideal' have made it hard for many viewers to accept that ancient Greek sculpture really was so very brightly coloured. But neoclassicists who praised the pure white beauty of bare marble and the noble austerity of ancient architecture were really imposing nineteenth century aesthetics and morality onto ancient Greek art and culture.

We have inherited those ideals and a particular way of viewing Greek sculpture – one which often makes it difficult to look beyond the glossy radiance of statues which long-ago lost their paintwork. Resistance lingers on today.

The cultural baggage attached to the perceived whiteness of classical sculpture is long overdue a reassessment. Rethinking colour is just one way to do so.

Alternative Reconstructions

Recent research has revealed very different reconstructions of the Peplos Kore's polychrome decoration.

Prof Vincenz Brinkmann and the Polychromy Research Project team have used raking light, where light is shone at an angle onto the surface of the sculpture to reveal raised paint shadows, to examine the original Peplos Kore and reveal evidence for paintwork not visible to the naked eye. The result has been a very different reconstruction to our own Painted Peplos Kore, and one which has toured the world as part of the popular Gods in Colour exhibition.

Brinkmann reconstructs the Peplos Kore with a yellow dress and a series of friezes of mythical animals, riders and hybrids on the skirt. He interprets her dress as not a peplos but an ependytes: a type of robe, worn open over an underdress (in this case, decorated with friezes) and with a matching cloak worn over the shoulders. The ependytes is not the attire of mere mortal women but of goddesses, raising the possibility that the Peplos Kore should be understood as Athena or Artemis. It is now sometimes referred to as the Ex-Peplos Kore as a result of these investigations.

The Akropolis Museum in Athens has also continued to conduct scientific analysis of the statues in its collection, including the Peplos Kore, and has produced its own digital reconstructions – and opted for subtler coloration in softer colours, with paint restricted to only the decorative details to allow the original marble to shine through.

Further Reading

MOCA Cast (no.34a)

- Robert M Cook (1976), 'A supplementary note on meniskoi', Journal of Hellenic Studies 96, pp.153-4

- Mary Beard (2008), 'Painted Cast of the Peplos Kore', in Roberta Panzanelli (ed.), The Color of Life: Polychromy in Sculpture from Antiquity to the Present, The J. Paul Getty Museum, pp.127-7, no.14

Original (Athens no.679)

- Brunilde Sismondo Ridgway (1977), 'The Peplos Kore, Acropolis 679', The Journal of the Walters Art Gallery 36, pp.49-6

- Robert M Cook (1978), 'The Peplos Kore and its dress', Journal of the Walters Art Gallery 37, pp.84-7

Other reconstructions

- Vincenz Brinkmann (2008), 'Reconstruction A of the Peplos Kore and Reconstruction B of the Peplos Kore', in Roberta Panzanelli (ed.), The Color of Life: Polychromy in Sculpture from Antiquity to the Present, The J. Paul Getty Museum, pp.128-130, nos.15 and 16

- Vincenz Brinkmann & Raimund Wünsche (2004), Bunte Götter: Die Farbigkeit Antiker Skulptur, pp.53-9