From pumice to LEGO

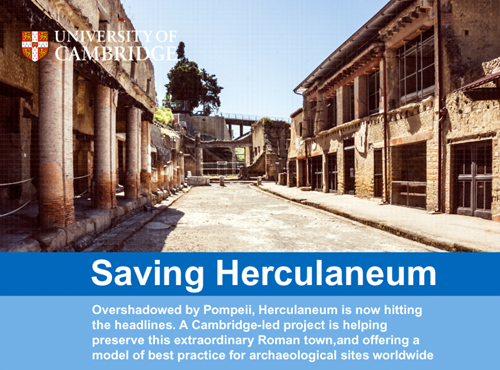

Herculaneum was overwhelmed by the same eruption of Vesuvius in AD 79 as neighbouring city Pompeii. But while Pompeii has become a household name, Herculaneum is less well known.

The Herculaneum Conservation Project (HCP) has now raised Herculaneum’s profile, conserved the site and become a model of best practice. Set up in 2001 thanks to the enthusiastic support of David Packard by the Packard Humanities Institute, the project combines conservation, research and public outreach in an innovative way.It is led by Professor Andrew Wallace-Hadrill of the Faculty of Classics.

In 2013, Wallace-Hadrill’s BBC2 documentary The Other Pompeii: Life and Death in Herculaneum attracted 2.7 million viewers. The project’s teaching materials are used in Italy, and in Australia where Pompeii- Herculaneum is studied by 11,000 Australian school children a year. Wallace-Hadrill was also involved in the exhibition Pompeii and Herculaneum: Life and Death at the British Museum. It was screened live to UK schools and cinemas in the USA and Canada. To top it all, in 2015 Wallace-Hadrill was immortalised in plastic in ‘LEGO Pompeii’ at the University of Sydney’s Nicholson Museum.

From crisis to conservation

Although destroyed at the same time as Pompeii, Herculaneum is different. Built on a smaller scale than its sprawling neighbour, Herculaneum affords an intimate insight into Roman urban society. And while Pompeii was covered by a shallower layer of ash and excavated over 200 years ago using pre- scientific techniques, Herculaneum was buried more deeply and excavated more recently, allowing archaeologists to study the organic materials – from wood to fossilised faeces – that have survived.

While working in Pompeii during the late 1990s, Wallace-Hadrill became increasingly concerned about the critical state of both sites. Caring for an archaeological site – which is decaying rapidly because it was never built to survive – is an immense challenge. But he realised that without prompt action, key parts of Herculaneum would be lost.

Out of crisis, the HCP was born and while the bulk of the project’s work would be delivered by Italian personnel, outside input from Wallace-Hadrill was judged key to overcoming bureaucratic and legislative red tape, and building relationships with Herculaneum’s modern inhabitants.

Local ownership

Since 2001, the project has focussed on developing better conservation strategies for Herculaneum. Through conservation it has deepened our understanding of Roman urban life and helped engage the public, both locally and internationally.

Although the project is not driven by a research agenda, research is an integral by-product of conservation. By looking at things more carefully – and intervening physically – conservation exposes new information. Digging a drain at Herculaneum, for example, uncovered a sewer full of human waste, giving archaeologists a rich insight into its inhabitants’ diets.

Using this and other new finds, Wallace-Hadrill’s 2011 book Herculaneum: Past and Future offers a fresh overview of Herculaneum’s urban history and development.

As well as generating research, conservation at Herculaneum is intimately linked with outreach. Archaeological sites are often viewed as impediments to modern life. At Herculaneum, however, the project has showed that involving and informing visitors can create a sense of local ownership that will ensure the site is cared for in the future.