A project in Classics is currently exploring and examining York’s Roman-period history. Centred on the comprehensive re-mapping of the ancient cityscape, the Roman York Beneath the Streets Project (RYBS) will gain a better understanding of the form, extent, and layout of this urban centre, one which at the time included both a military fortress and a colonia. Led by Principal Investigator, Martin Millett (Cambridge), and Co-Investigator, John Creighton (Reading), with Thomas Matthews Boehmer (Cambridge) as Postdoctoral Research Associate, this three-year project is funded by the Arts and Humanities Research Council (2021-2024), and represents an important collaborative venture. Cambridge’s Faculty of Classics has teamed up with the Department of Archaeology at the University of Reading in order to work with colleagues at York Archaeology (a commercial archaeological unit), York Museums Trust, and the University of Ghent, in a partnership that will create a much fuller vision of Eboracum than has been hitherto available to either the researcher or the general public (Figure 1).

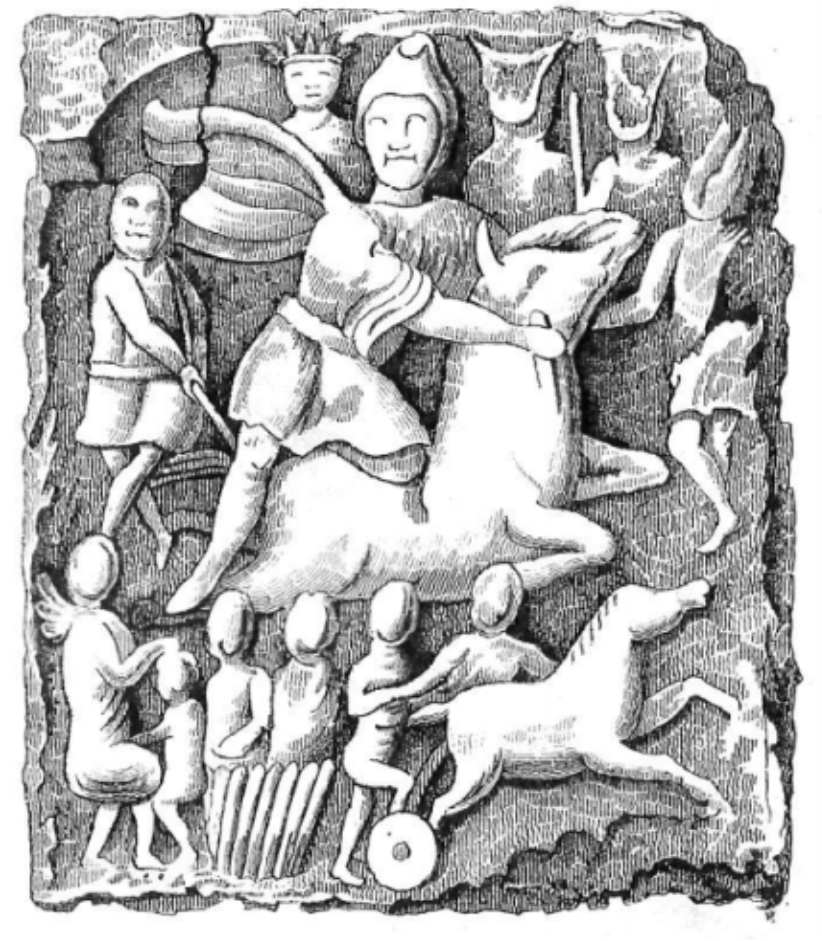

Figure 1: A drawing of the stone relief depicting Mithras found beneath Micklegate, York, in 1747 (Wellbeloved 1842, Plate IX). The site sits within the colonia.

Underpinning RYBS’s investigations are two innovative Ground-Penetrating Radar surveys which will reveal the buried landscapes beneath people’s feet. One of these surveys targets green spaces in York’s historic core whilst the other has snuffled across sixteen kilometres of the city’s streets in a bid to understand the character of the Roman-period archaeology that lies under the present tarmac. As part of this process, and during the course of the 2022 summer, Lieven Verdonk (Ghent) tested out a series of GPR arrays on an area of ground adjoining the present Minster Library (Figure 2). In the course of 2023, his work will extend to cover the rest of the area around the Minster in addition to the Museum Gardens. However, initial findings from the patch of grass next to the Library have already located the faint traces of structures underneath the palace of the medieval archbishops.

Figure 2: Lieven Verdonk (Ghent) tests out an innovative GPR array near to the Minster Library.

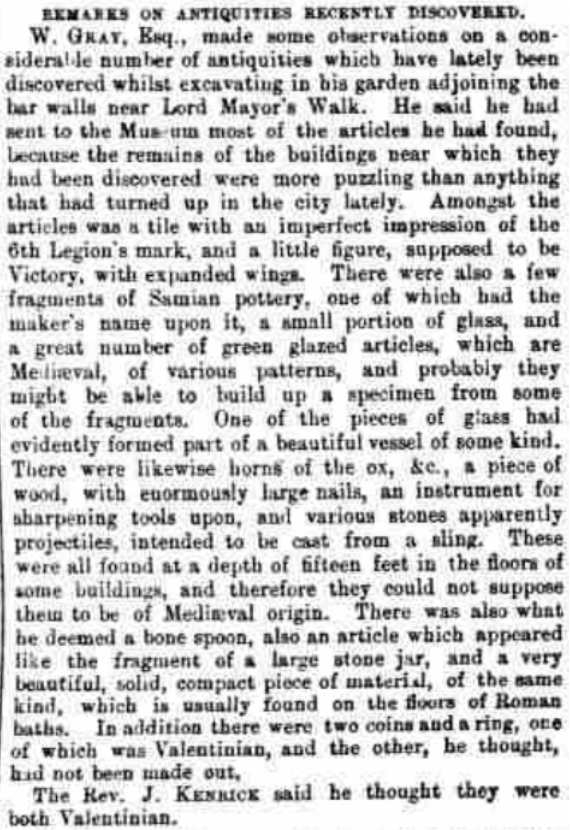

Another key part of RYBS is the location and assessment of antiquarian and early archaeological findings from the city. Significant local figures, including the York city surgeon, Francis Drake (1696 - 1771), and the newspaper proprietor: William Hargrove (1788 - 1862), were very involved in recording Roman remains during the 18th and 19th centuries. Matthews Boehmer’s research has shed new light on the importance of these sources. For example, a copy of an inked 1864 map of the city (currently archived in the York Explore Library), was updated into the early 20th century. Crucially and helpfully, it reveals exact locations for several burials and buildings unearthed in the course of that time. Indeed, one of the buildings that has been drawn on the map is found to be in a different place to where current reconstructions of York position it. By comparing the siting of the building on the map to the newspaper reports of its excavation (Figure 3), as well as the trade directories of the period, we now have a much clearer sense of this part of the fortress’s northern intervallum area.

Figure 3: Newspaper cutting from page 10 of the York Herald, Saturday 8th June 1861. This records the excavation of a building near to the present Monkgate Bar on the north-eastern side of the fortress. The Herald was the newspaper owned by William Hargrove.

This kind of closely focussed exploration which includes considering different sorts of source: older maps and plans, antiquarian observations and newspaper reports, with both each other and modern archaeological excavations, is strikingly useful when it comes to considering whole blocs of the city. York’s present-day south-western portion: stemming down from Micklegate Bar to Dringhouses, has been known since the early 17th century for the number of its Roman-period burials. And yet, what has been less clear is how this landscape of the dead fits in with the rest of the built environment from that era. Early indications are that there was very little grand design or layout of this area in either the early Roman period or later on. Some of the graveyards encountered here do not appear to reference the general line of the road leading into York, and those roads appear to be on subtly different alignments to what had been expected.

What is being found therefore in the RYBS is that Eboracum, the town where Septimius Severus stiffed and Constantine was acclaimed, has not only a more complicated and interesting relationship with empire, but that there is much more that stills need to be understood about Roman-period urban entities in the north of the imperial world.

For those in Yorkshire, there will be opportunities for volunteering with the project in partnership with York Archaeology in the near future. Otherwise, please keep up-to-date with our Instagram, @Roman_york_beneath_streets.